Key Messages – Main Areas of Change

Key Messages – Main Areas of Change

![]() Download these notes as a PDF:

Download these notes as a PDF:

DfE 8 Fostering and Adoption Topic 8 monitoring and enabling capacity to change

Topic 8: Monitoring and enabling parenting capacity

Assessing parents’ capacity to change (PDF download)

A practical tool to help professionals with the four-stage process is available to download.

- Most children are in the looked after system because their birth parents are not parenting well enough to meet their child’s needs and keep them safe.

- Returning home will be an aspiration for most children and for their birth parents.

- Reunification is attempted for around a third of children leaving care; however, around two thirds of maltreated children who return home are subsequently readmitted to care (Davies and Ward 2012).

- We know that repeated, failed attempts at reunification have an extremely detrimental effect on children and young people’s well-being.

- Decisions to reunify maltreated children should not be made without careful assessment and evidence of sustained positive change in the parenting practices that had given concern (Wade et al, 2010).

This briefing focuses on one element of assessment – understanding parents’ capacity to change.

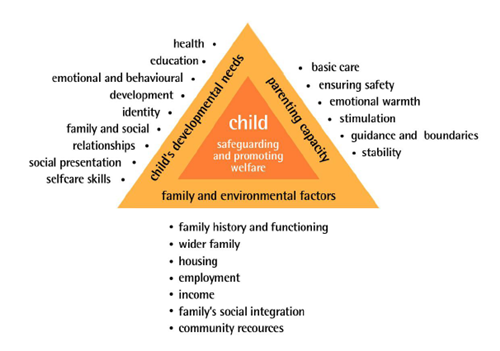

The government’s statutory guidance Working Together to Safeguard Children (2013) sets out the processes and statutory context for assessment. The Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and their Families (see diagram below) is the underpinning structure to support examination of children’s developmental needs, parents’ capacity to respond appropriately, and family and environmental factors. These three elements are inter-related – they cannot be considered in isolation

Three concurrent activities underpin effective assessment:

- Engaging the child and family. (Partnership working is key to successful engagement.)

- Safeguarding – continuing to monitor a child’s safety throughout. (This means re-examining initial decisions on the immediate safety of the child.)

- Collaborating – ensuring meaningful engagement with the range of professionals involved with the child and family.

(Davis and Day, 2010; Buckley et al, 2006)

What is ‘capacity to change’?

‘Parenting capacity’ and parents’ ‘capacity to change’ are two linked but distinct aspects of an assessment with high-risk families.

Assessment of parenting capacity considers the parents’ ability to provide ‘good enough’ parenting in the long term. A survey of practitioners has identified four key elements of good enough parenting:

- meeting children’s health and developmental needs

- putting children’s needs first

- providing routine and consistent care

- acknowledging problems and engaging with support services (Kellett and Apps 2009, cited in NSPCC, 2014).

The assessment of capacity to change adds a time dimension and asks whether parents – over a specified period of time and if provided with the right support – are ready, willing and able to make the necessary changes to ensure their child’s well-being and safety.

The main aim of an assessment of parental capacity to change is to reduce uncertainty. When an assessment of parenting capacity – carried out at one point in time – identifies both weaknesses and strengths in the family, it is difficult to predict future outcomes. An assessment of capacity to change provides parents with the opportunity to show whether they can address concerns identified in an assessment of parenting capacity.

Capacity to change requires that parents:

- recognise the need to change and be willing to engage in the change process

- have the ability to make changes – for example, learn new parenting skills or engage social support

- put effort into the change process

- sustain initial effort over time.

Practitioners assessing capacity to change need to:

- ensure they monitor change by having clear and observable goals by which to determine whether change has occurred

- understand that parents may be unwilling to recognise and address some aspects of their situation

- recognise that parents with multiple problems may find the challenge of making changes overwhelming

- acknowledge that some parents may show an initial willingness to engage in the change process but fail to make changes that indicate a capacity to improve their parenting

- remember that willingness to work with a particular professional or participate in a particular programme should not be equated with capacity to change.

(Buckley et al, 2006; Barlow and Scott, 2010)

Assessment of capacity to change will be supported by working in partnership with parents to reach an understanding of their:

- views of presenting problems

- goals and values

- hopes and beliefs about whether the situation can improve

- views of available alternatives.

Whatever the ultimate permanence pathway for a child, partnership working will support parents’ understanding of and engagement with decisions made.

(Littell and Girvin 2006, cited in Barlow and Scott, 2010)

Assessment frameworks

In order to assess capacity to change professionals must first identify which areas of family life need to change if the children are to be safe and adequately nurtured. There are many linked aspects of a family’s situation to consider, so professionals need a framework with which to make sense of the information on which they base their judgements. Problems can emerge in any or all domains of family life. It is vital that these domains are not seen as separate in reality, as we need to explore the interconnections and interactions between the different areas (Turney et al, 2011).

In addition to the Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and their Families (see above), there are many other frameworks to support assessment of need and of risk, some designed for specific aspects of practice.

The use of a framework for cross-sectional assessment supports the first stage in what Harnett (2007) has mapped out as a four-stage process for assessing parents’ capacity to change.

A four-stage process for assessing capacity to change:

When a multiagency assessment results in equivocal information about parents – in other words, when risk factors don’t clearly outweigh protective factors, or vice versa – there is uncertainty. Drawing on the science of decision-making (eg Baumann et al, 2011), we also know that individual practitioners or teams making decisions under conditions of uncertainty are prone to error and bias.

This leads us to the conclusion that the assessment process must aim to increase certainty. And the most reliable way in which to reduce uncertainty is to provide families with an opportunity to demonstrate change. Harnett’s (2007) four stages outline a protocol for assessing a ‘family’s actual capacity to change, including an evaluation of the parent’s motivation and capacity to acquire parenting skills’.

Stage One:A cross-sectional assessment is undertaken using an assessment framework.

Stage Two:Short-term goals are identified in collaboration with the family and are made explicitly clear.

Stage Three: A time-limited intervention or support plan is put in place to ensure that families have the opportunity to demonstrate goal achievement.

Stage Four: Goal progress is reviewed and measures are re-administered to ascertain if capacity to change has been demonstrated.

To support parents to make changes and to support practitioners to assess whether meaningful change is achieved in the agreed timeframe, this process includes two important elements:

- Using standardised measures at Stage One to take an initial baseline measurement of relevant aspects of the family’s situation. The same measures are used again at Stage Four to assess the extent of change achieved.

- Vital information about a family’s capacity to change is obtained by setting meaningful and measurable goals at Stage Two and systematically monitoring goal attainment. Goal progress is then reviewed at Stage Four.

The next section explores these four stages in more detail.

Stage One: Assessment of the family’s current functioning

Alongside the cross-sectional assessment, practitioners use standardised measures to ‘take a baseline’ on particular aspects of parent or family functioning. Using these measures supports practitioners to apply Structured Professional Judgement.

What is Structured Professional Judgement?

Barlow et al’s Systematic Review of Models of Analysing Significant Harm (2012) strongly endorsed professional judgement and partnership working with families as vital elements in assessment and intervention. But the review also makes clear that ‘unaided clinical judgement in relation to the assessment of risk of harm is now widely recognised to be flawed’ (p20). Professional judgement alone is not enough, just as standardised tools without professional expertise and skills can never be enough. This approach combines professional judgement with the use of standardised measures to assess child development and family functioning.

Effective development of Structured Professional Judgment requires:

- specific guidance on using standardised measures in the context of partnership working with children and families

- the development of a suite of standardised measures to be used at different stages in the assessment process

- organisational and management support with effective supervision and high-quality training and guidance.

Accurately measuring change

In the Four Stage process, standardised measures are used to obtain baseline information which can then be re-assessed following goal-setting and a period of support. In order to use measures accurately, we need to make the conditions at first and second measurement as similar as possible. This might include:

- Environment: time of day, who is around, what else is going on. Ask parents to turn down/off the TV/music. If possible go into a quieter space.

- Help parents understand the purpose of the measures: parents may be inclined to ‘fake good’ in their responses to questions about their emotional well-being, substance use and other potential problems. This is understandable but creates problems as:

(i) it is difficult to gain an accurate picture of the issues facing the family and how best to support them

(ii) minimising problems can be interpreted as a lack of cooperation or deliberately misleading professionals.

- Explain how you are using the measures – that you want them to complete the measures to ‘see how things are going right now’ and that you will repeat the measure in some weeks or months ‘to help us understand how much change you have been able to make’. Explain that this is an important way of making the assessment fair and accurate. For example, parents may feel they were trying in the past but this wasn’t recognised, or that certain professionals just didn’t like them. This approach can address that sort of concern.

- Use a strengths-based approach: parents are more open to an approach that shows empathy with and seeks to build on strengths within the family.

Stage Two: Specifying targets for change: Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS)

Work in partnership with the family to set clearly specified targets for change. These should relate directly to the problems the family is facing and be agreed to be meaningful by the family and the professionals involved (Harnett, 2007).

Setting goals with families:

- Identify goals for change that can be ‘operationally defined, observed and monitored over time’ (ideally by multiple independent informants such as teachers, foster carers and other professionals working with the family) (Harnett, 2007). Goals set should be manageable as well as meaningful.

- Too easy: reaching trivial targets will not give useful information about the capacity for change.

- Too hard: goals that are too far beyond realistic expectations for this parent in the agreed timeframe will be overwhelming and ‘effectively set the family up for failure’ (Harnett, 2007).

Defining and agreeing goals:

- Don’t set up false expectations of success: it is to be expected that a proportion of families will fail to achieve agreed targets for change.

- Ensure regular monitoring of progress: feedback to parents will highlight any difficulties throughout the assessment process. With regular feedback, a decision that the parents will not achieve a minimal level of parenting within an acceptable timeframe has, at least, been a transparent process.

(Harnett, 2007)

Stage Three: Intervention or support to address the needs identified

‘Poor parenting, drug or alcohol misuse, domestic violence, and parental mental health problems, all increase the chance of harm when the child returns home. Farmer et al found that 78 per cent of substance-misusing parents abused or neglected their children after they returned from care compared to 29 per cent of parents without substance misuse problems … UK studies demonstrate instances of children returning to households with a high recurrence of drug and alcohol misuse (42 and 51 per cent of cases respectively), but where only 5 per cent of parents were provided with treatment to help address these problems.’ (NSPCC, 2012)

Effective support will include:

- targeted provision to address the concerns identified (eg domestic abuse, drug or alcohol problems, mental health issues, managing children’s behaviour)

- practical support (eg to address housing issues, financial problems)

- support from foster carers and schools to help children prepare for a successful return home

- provision of support for as long as is needed for a problem to be sustainably addressed.

Themes running through the evidence suggest the kinds of approach that are likely to be most effective. These include:

- tailoring support to the specific needs of families

- strengths-based approaches: build on the positive aspects of family life that exist, even in the most troubled families

- support and challenge: effective key working develops sustained relationships of trust in which the worker both supports the family and challenges them to change entrenched negative behaviours

- proactive case management: don’t let long-term cases lose focus – regular review with colleagues, supervisor or team manager is essential to avoid ‘drift’.

Stage Four: Review progress and measure change

- Re-administer the standardised measure(s) used at Stage One (or, where available, use the follow-up version).

- Review the results of the GAS procedure: to what extent have the goals agreed and set together with the family been met?

Stage Four is an opportunity to:

- review progress

- build upon the evidence gathered with new information

- revisit earlier assumptions in the light of new evidence

- take action to revise decisions in the best interests of the child.

Conclusion

Decisions should always be led by what is in the child or young person’s best interest. Where a decision is taken that a child will return home, practice should take account of evidence on factors that appear to support enduring reunifications. These include:

- Ensuring reunification takes place slowly, over a planned period, allowing time for a well-managed and inclusive planning process.

- Providing specific support, often of quite high intensity, both to children and young people and to their parents, based on the needs evidenced in the risk assessment.

- Care plans that set out clear expectations of monitoring and support arrangements after a child returns home. This should include regular visits from a consistent key worker.

- Cases should remain open for a minimum of one year after a child returns home.

- Wade et al (2010) found that most difficulties emerged within the first few months of reunion and problems early in reunion predicted poor well-being at follow-up four years later.

- Where changes are not sustained or parents fail to comply with treatment programmes, an early assessment of the longer-term potential for the child should be made to prevent drift and further deterioration. Repeated attempts at reunification should be avoided. In Wade et al’s study, the children who experienced the most unstable reunifications were among those to have the worst overall outcomes. This is damaging for children and increases the risk that they will not be found a permanent placement – or, if they are, that it will not be successful.

- Where there is strong evidence of serious emotional abuse or past neglect, Wade et al’s study found that these children did best if they remained in care

(Wade et al, 2010; NSPCC, 2012)

Exercise

Exercise

![]() Download these notes in the topic PDF:

Download these notes in the topic PDF:

DfE 8 Fostering and Adoption Topic 8 monitoring and enabling capacity to change

![]() Download the exercises as a Word DOCX file:

Download the exercises as a Word DOCX file:

DfE Fostering and Adoption Topic 8 monitoring and enabling capacity to change exercises 02.07.14 .DOCX

Download the exercises as a Word 97-2003 DOC file:

DfE Fosterting and Adoption 08 monitoring and enabling capacity to change exercises 02.07.14 .DOC

Standardised assessment tools

Methods

Suitable for a group discussion in a team meeting or facilitated workshop.

Learning Outcome

Understand the range of standardised assessment tools which are used locally and identify how they can be used.

Time Required

45 minutes.

Process

Review the information in section 1 on standardised assessment tools and use the questions in section 2 as prompts for a group discussion.

- Standardised assessment tools

The approach set out in the briefing Monitoring and enabling capacity to change includes the use of standardised assessment tools as part of a four stage process for assessing capacity to change (Harnett 2007).

The standardised assessment tools that accompanied the Assessment Framework (DH et al, 2000) are:

- Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: widely used, it assesses emotional and behavioural problems in children and adolescents using five scales: pro-social behaviour, hyperactivity, emotional problems, conduct problems, and peer problems.

- Parenting Daily Hassles Scale: aims to assess the frequency, intensity and impact of 20 potential parenting ‘daily’ hassles experienced by adults caring for children.

- Home Conditions Assessment: addresses various aspects of the home environment (for example, smell, state of surfaces in house, floors).

- Adult Well-being Scale: looks at how an adult is feeling in terms of depression, anxiety and irritability.

- Adolescent Well-being Scale: involves 18 questions relating to different aspects of a child or adolescent’s life and aims to give practitioners more insight into how an adolescent feels about their life.

- Recent Life Events Questionnaire: is intended to help with compiling a social history and giving a better understanding of the family’s current situation by looking at whether events still affect the person.

- Family Activity Scale: explores the environment carers provide through joint activities and support for independent activities, and the cultural and ideological environment in which children live.

- Alcohol Scale: looks at how alcohol impacts on the individual and on their role as a parent to help to identify alcohol disorders and hazardous drinking habits.

- What tools are available in your area?

To what extent is structured professional judgement accepted practice with social workers, managers and legal representatives in your agency?

- Which of the standardised assessment tools listed above do you use?

- What other tools do you use?

- Are all relevant colleagues:

- aware of the tools available and

- trained in how to use them?

- If not, how could you increase awareness and understanding?

- To what extent does your supervisor support the use of standardised tools in practice?

- How can your agency support shared understanding and use of standardised tools in work with children and families where reunification with the birth family is under consideration?

Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS) case study based exercise for social workers

![]() Download the GAS exercise as a Word DOCX file:

Download the GAS exercise as a Word DOCX file:

DfE Fostering and Adoption 08 Goal Attainment Scaling 02.07.14 .DOCX

Download the GAS exercise as a Word 97-2003 .DOC file:

DfE Fostering and Adoption 08 Goal Attainment Scaling_97-2003 02.07.14 .DOC

![]() Download these GAS exercise as a PDF file:

Download these GAS exercise as a PDF file:

DfE Fostering and Adoption 08 Goal Attainment Scaling 02.07.14 .PDF

Methods

Suitable for a small group discussion as part of a facilitated workshop.

Learning Outcome

To practise using Goal Attainment Scaling to set meaningful and measurable goals.

Time Required

40 minutes for discussion plus 20 minutes for feedback

Process

The approach set out in the briefing Monitoring and enabling capacity to change includes the use of Goal Attainment Scaling as part of a four stage process for assessing capacity to change (Harnett 2007). A worked example of the GAS template is included to give a sense of how this might work in practice.

Give each group a hand-out of the case study for Rosie, as well as a copy of the activity.

Ask each group to appoint someone to feedback their ideas.

Activity brief

Using the Rosie case study, fill in the GAS template to set meaningful and measurable goals, which will support the care plan and provide evidence on Lena’s capacity to make the changes required to keep Rosie safe if she is to return to her care.

- Who will you involve in setting these goals?

- How will you monitor the arrangements and what is a suitable timescale for achieving the goals outlined?

- How can the child’s social worker and supervising social worker work together – and with Lena – to support Andrea in keeping Rosie safe and setting and maintaining boundaries around contact and behaviour generally?

- What specific emotional support needs might Lena have? How can these be explored sensitively?

What will be the next steps if a) goals are reached b) goals are not reached?

Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS) worked example

Refer to the worked example which you can find this on pages 4-5 of the Exercises document.

You can complete the GAS template for the exercise which is on page 6.

Adapted from an example from Barlow, J. (2012) [Presentation at Home or Away: Making difficult decisions in the child protection system Partnership Conference] 22 February.

Presentation slide deck

Presentation slide deck

![]()

Download the slides as a PowerPoint .pptx file (3.5mb)

Alternative PowerPoint 97-2003 format:

DfE Fostering and Adoption Topic 8 monitoring and enabling capacity to change slides_97-2003 .PPT

References

References

![]() Download these notes in the topic PDF:

Download these notes in the topic PDF:

DfE 8 Fostering and Adoption Topic 8 monitoring and enabling capacity to change

- Barlow J and Scott J (2010) Safeguarding in the 21st Century: Where to now. Dartington: Research in Practice

- Barlow J, Fisher J and Jones D (2012) Systematic Review of Models of Analysing Significant Harm. (Research Report DFE-RR199) London: Department for Education

- Baumann D, Dalgleish L, Fluke J and Kern H (2011) The Decision-making Ecology. Washington, DC.

- Brown L, Moore S and Turney D (2012) Analysis and Critical Thinking in Assessment. Resource pack. Dartington: Research in Practice

- Buckley H, Horwath J and Whelan S (2006) Framework for the Assessment of Vulnerable Children & their Families: Assessment tool and practice guidance.Dublin: Children’s Research Centre, Trinity College

- Cleaver H, Unell I and Aldgate J (2011) Children’s Needs – Parenting Capacity. Child Abuse: Parental mental illness, learning disability, substance misuse, and domestic violence. (2nd edition) London: The Stationery Office

- Davis H and Day C (2010) Working in Partnership with Parents. London: Pearson

- Davies C and Ward H (2012) Safeguarding Children across Services. London: Jessica Kingsley

- Harnett P (2007) ‘A Procedure for Assessing Parents’ Capacity for Change in Child Protection Cases’ Children and Youth Services Review 29 (9) 1179-1188

- Harnett P and Dawe S (2008) ‘Reducing Child Abuse Potential in Families Identified by Social Services: Implications for assessment and treatment’ Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention 8 (3) 226-235

- HM Government (2013) Working Together to Safeguard Children: A guide to inter-agency working to safeguard and promote the welfare of children. London: Department for Education

- Kellett J and Apps J (2009) Assessments of Parenting and Parenting Support Need: A study of four professional groups. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation

- Littell J and Girvin H (2002) ‘Stages of Change: A critique’ Behavior Modification 26 (2) 223-273

- Littell J and Girvin H (2006) ‘Correlates of Problem Recognition and Intentions to Change Among Caregivers of Abused and Neglected Children’ Child Abuse & Neglect 30 (12) 1381-1399

- NSPCC (2012) Returning Home from Care: What’s best for children. London: NSPCC

- NSPCC (2014) ‘Assessing Parenting Capacity’ (NSPCC online factsheet) London: NSPCC

- Turney D, Platt D, Selwyn J and Farmer E (2011) Social Work Assessment of Children in Need: What do we know? Messages from research. London: Department for Education

- Wade J, Biehal N, Farrelly N and Sinclair I (2010) Maltreated Children in the Looked After System: A comparison of outcomes for those who go home and those who do not. London: Department for Education